Electric Daisy Carnival Las Vegas Getty Images

Electric Daisy Carnival Las Vegas Getty Images

$3.2 billion. That is how much the music festivals of Insomniac, a dance-music promoter, generated in economic activity in the U.S. in recent years. The firm asked Beacon Economics, a consulting firm, to crunch the numbers on how 48 of their events contributed to the economy—everything from traveling fans splurging on restaurants to local firms seeing a bump in business.

Though a couple billion dollars is a drop in the bucket (America’s gross domestic product totals more than $16 trillion), it’s pretty impressive for bunches of kids bopping around to the beats of Avicii and Tiësto.

“We found there was a very significant impact, ” says Jordan Levine, lead author of Beacon Economics’ report, which was released today. Between 2010 and 2014, Mr. Levine measured roughly $327 million in direct spending by Insomniac for these 48 events, including Electric Daisy Carnival Las Vegas. Festival attendees spent around $866 million over this period on things such as transportation and hotels (the cost of tickets was excluded). Using these numbers, Levine then estimated the “downstream” or indirect spending impacts using a commonly used economic model whose underpinnings rely on a U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis approach.

The upshot: The overall economic impact of Insomniac’s spending was $885 million, and that of festivalgoers’ spending was $2.3 billion. The equivalent of some 25, 000 full-time U.S. jobs were created. And Insomniac’s 48 events supported some $180 million in taxes for state and local governments.

And that’s just Insomniac.

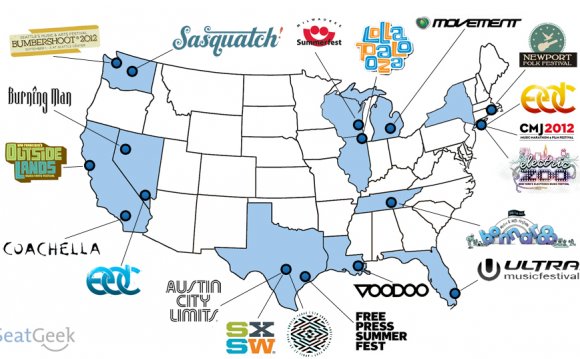

Music festivals have matured since the early 1990s and, in many cases, become sustainable businesses—prompting a buying spree by live-music juggernauts Live Nation Entertainment Inc. and AEG Live. City officials should take notice, if they haven’t already. Beacon Economics’ analysis suggests that festivals can, in many cases, boost consumption and generate jobs.

Many music fans travel to attend festivals, which triggers vacation-style spending. When Insomniac spends millions of dollars on things such as equipment rental, construction, and security, that can generate spending by suppliers filling Insomniac’s orders, Levine says. (A food caterer hired by Insomniac, for example, would have to purchase ingredients locally, etc.)

Some caveats.

It’s hard for economists to estimate the impact of a new power plant in a city—let alone a big music festival. Economic impacts can be fleeting: Businesses may make existing workers toil longer, or hire short-term staff. It’s also important whether local workers are used or not.

The Beacon Economics report says the jobs impact of Insomniac’s 48 events was measured “in terms of full-time equivalent positions and is therefore a conservative estimate of the total number of jobs supported.” In other words, Levine is deliberately undercounting jobs, since many of them will be short-term. Also, in his analysis of “downstream” spending, he’s adjusting for the fact that some of the spending would have happened anyway. (Beacon Economics had data on whether Insomniac festivalgoers were locals or tourists based on surveys.)

RELATED VIDEO